|

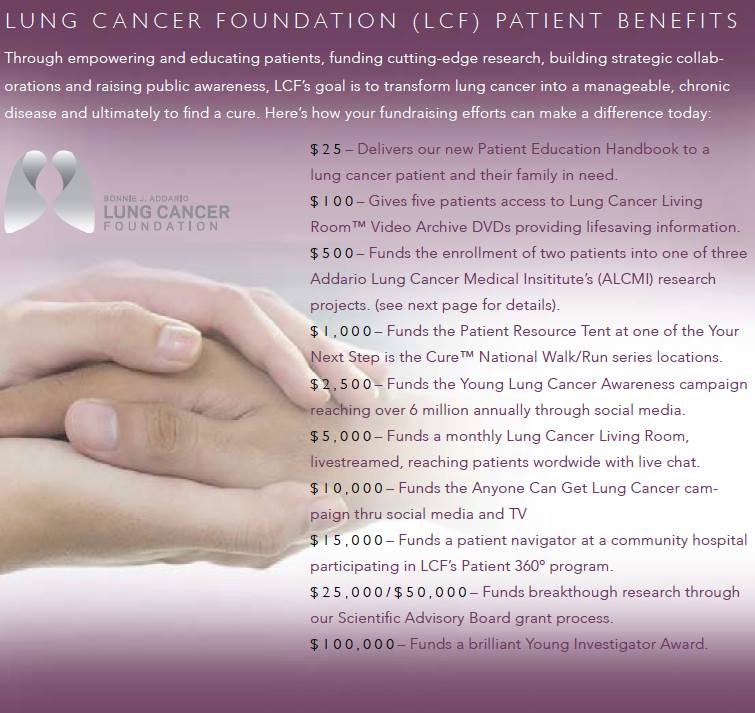

We are about halfway through Lung Cancer Awareness Month and I would like to offer some information about a fantastic organization. If you are reading this, you likely know about this group. But, even if you do, I encourage you to sit back with your favorite beverage and take a few minutes to watch the video at the end of this post. When supporting any cause or charity with a financial gift, prudent questions are “Where does the money go?”, “How effective is the organization?”, “Is it worthy of my support?”, "What are they doing?", "What have they done?" I ask these questions myself before choosing to financially support any charitable cause. This video, narrated by their Senior Director of Patient Services and Programs, Danielle Hicks, does an excellent job of answering these questions for The Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation (ALCF). My family and I met the Addarios shortly after our mother died in 2007. We were immediately struck by their sincerity, warmth - and tenacity. But, we were also impressed by their team and how they were attacking the lung cancer problem with intelligence and professionalism. In 2010, The Joan Gaeta Lung Cancer Fund proudly became an affiliate of ALCF. And, since 2012, those of you in Georgia have been able to order Lung Cancer Awareness License Plates - a first in the United States. 85% of the annual tag fee goes to ALCF’s research institute. You can also donate directly to ALCF via this link. Please to watch the video and consider a donation during this important month. Thank you, Joseph A. Gaeta The Joan Gaeta Lung Cancer Fund

0 Comments

Please help us in our continuing effort..... Donate today. ALCMI Puts Spotlight on Lung Cancer in Young Adults San Carlos, Calif. (July 23, 2014) – The Addario Lung Cancer Medical Institute (ALCMI) today launched a new study, the Genomics of Young Lung Cancer, to understand why lung cancer occurs in young adults, who quite often are athletic, never smokers and do not exhibit any of the known lung cancer genetic mutations. ALCMI, a patient-centric, international research consortium and partner of the Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation (ALCF), is facilitating this first-of-its-kind, multi- institutional, prospective genomic study in order to identify new genome-defined subtypes of lung cancer and accelerate delivery of more effective targeted therapies. “It’s heartbreaking when you meet young adults with lung cancer, who should have their full lives ahead of them but instead are fighting for their lives because of the lack of lung cancer treatments,” said Bonnie J. Addario, stage 3B lung cancer survivor and founder of ALCMI and the ALCF. “This groundbreaking study will investigate why young adults under the age of 40 are getting lung cancer and whether they have a unique cancer subtype, or genotype, that can be treated differently.” Our evolving understanding of the disease and new molecular tools suggest that young age may be an under-appreciated clinical marker of new genetic subtypes. An important goal for this research study is to reveal new lung cancer sub-types of lung cancer requiring distinct treatment strategies. “Leveraging this study as a proof of principle, ALCMI is also characterizing other specific patient populations to support emerging data that lung cancer diagnostic and therapeutic interventions are more effective when individualized, and personalized approaches are brought to bear," Steven Young, President and COO of ALCMI, who also points out this study represents a unique public-private collaboration between the ALCMI consortium and Foundation Medicine, Inc. The Genomics of Young Lung Cancer study is centrally managed by ALCMI while the Principal Investigator (study leader) is Barbara Gitlitz, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Southern California, Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center. "This study lays the groundwork for discovery of novel targetable genotypes as well as heritable and environmental risk factors for lung cancer patients under 40,” Dr. Gitlitz said. "We'll be evaluating 60 patients in this initial study and hope to apply our findings to a larger follow-up study in the future." Other investigators include Geoffrey Oxnard, MD, (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute), David Carbone, MD, PhD (The Ohio State University), and Giorgio Scagliotti, MD, PhD and Silvia Novello, MD (both at the University of Torino in Italy). Patients may enroll in the study regardless of where they live, and will not need to travel to any of the above institutions. For more information about the study, please contact Steven Young, president of ALCMI, at (203) 226-5765 or [email protected]. Lung cancer patients living in the United States will not need to travel to any of the above institutions to participate (but may do so), and may learn more at https://www.openmednet.org/site/alcmi-goyl. Individuals living outside the U.S. may contact ALCMI at [email protected] for information on how to participate. Lung Cancer Facts

About the Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation The Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation is one of the largest philanthropies (patient-founded, patient-focused, and patient-driven) devoted exclusively to eradicating Lung Cancer through research, education, early detection, genetic testing, drug discovery and patient-focused outcomes. The Foundation works with a diverse group of physicians, patients, organizations, industry partners, individuals, survivors, and their families to identify solutions and make timely and meaningful change. ALCF was established on March 1, 2006 as a 501c(3) non-profit organization and has raised more than $15 million for lung cancer research. To learn more, please visit www.lungcancerfoundation.org. About the Addario Lung Cancer Medical Institute The Addario Lung Cancer Medical Institute (ALCMI), founded in 2008 as a 501c(3) non-profit organization, is a patient-centric, international research consortium driving research otherwise not possible, evidenced by ALCMI's current clinical studies CASTLE, INHERIT EGFR T790M, and the Genomics of Young Lung Cancer. ALCMI overcomes barriers to collaboration via a world-class team of investigators from 22+ institutions in the U.S. and Europe, supported by dedicated research infrastructures such as centralized tissue banks and data systems. ALCMI directly facilitates research by combining scientific expertise found at leading academic institutions with patient access through our network of community cancer centers – accelerating novel research advancements to lung cancer patients. Originally published on June 24th, 2014 by Victoria Colliver at SFGate.com.

Victoria is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. --- Natalie DiMarco's only obvious risk factor for getting lung cancer was having lungs. Natalie DiMarcoDiMarco had been experiencing respiratory problems for months in 2010, but her doctors just assumed the mother of two had allergies. By the time she learned she had lung cancer, the disease had spread into her lymph nodes and reached the membranes that surround the lungs. "I'm young, didn't have any history of smoking, and that's why a doctor didn't X-ray me from the beginning," said DiMarco, now 36, who lives in Penngrove with her husband, daughters, ages 5 and 6, and a teenage stepson. An estimated 4,600 to 6,900 people under 40 in the U.S. are diagnosed every year with lung cancer that has no apparent cause. The disease appears to be quite different from the lung cancer found in longtime smokers and, aside from initial research that indicates that young patients, like DiMarco, tend to share certain genetic changes, the source remains a mystery. A new study just getting under way hopes to find out more about these patients, what they have in common and, potentially, why they get lung cancer. If researchers can find a common thread, or several, it could lead to more effective treatment or point the way to new targeted therapies. The $300,000 Genomics of Young Lung Cancer Study is small - just 60 patients - but the lead researchers hope it will help find the answers they're looking for and even help others with lung cancer, particularly the 15 percent of the nearly 230,000 Americans diagnosed with lung cancer each year who have never smoked. Addario Lung Cancer Medical Institute, a partner organization of theBonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation in San Carlos, initiated and is paying for the study along with Genentech. Not much is known. Bonnie Addario, who was diagnosed with lung cancer in her mid-50s in 2003 and founded the organizations that bear her name, said much is unknown about this population of patients because it's never been systematically studied. "We're hoping to find something that may be in another cancer or another disease that could be part of their therapy," she said. Dr. Barbara Gitlitz, a lead researcher of the study and director of the lung, head and neck program at theUniversity of Southern California's Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, said the disease should be thought about as its own entity. "We may discover that by looking at the genomics of these people, we may find driver mutations. We'll see patterns that might be specific to this population and we might see something new," she said. Time is of the essence, considering how devastating a lung cancer diagnosis is. Bonnie AddarioJust 15 percent of people diagnosed with lung cancer live longer than five years, in part because the disease is difficult to detect in its earlier stages and tends to be caught too late. That's particularly true among young people because no one's looking for it. "What we're hearing quite often is that they're athletes and they're very fit - the people you would least expect to have cancer, let alone lung cancer," Addario said. She added that the disease appears to be more common in young, nonsmoking women than in their male counterparts. Inspired by Cal athlete. Jill CostelloThe study was inspired by Jill Costello, a San Francisco native and varsity coxswain for UC Berkeley's women's crew, who died of lung cancer in 2010 at age 22, a year after she was diagnosed. Jill's Legacy, a subsidiary of Addario's foundation, was created in her honor to raise funds and awareness for lung cancer among young people. Researchers do know that young people and nonsmokers with non-small-cell lung cancer - the most common kind - typically have alterations in their genes that can affect how the disease is treated. The genetic mutation found most often - EGRF, for epidermal growth factor receptor - occurs in about 10 to 15 percent of non-small-cell lung cancer patients. But a host of other known mutations - ALK, ROS1, BRAF, HER2, MET, RET - have also been identified as contributing to lung cancer in young patients, said Dr. Geoffrey Oxnard, a lung cancer specialist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, also a lead researcher of the study. Drugs have been developed in recent years to "target" those mutations, or go after those specific cells to thwart their growth. The first EGRF therapies, AstraZeneca's Iressa, or gefitinib, was approved by federal regulators in 2003 followed by Roche's Tarceva, or erlotinib, in 2005. But even these relatively new treatments don't cure the disease; at most they buy time - from several months to five years - before the cancer returns. Oxnard said he hopes the study - which will test for more than 200 mutations - will not only show a pattern of these genetic alterations but also spotlight the necessity for young and nonsmoking people to get genetically tested after diagnosis, which is not routinely done in all centers. "We know comprehensive genetic testing has the potential to make a difference in any cancer patient, but we think in these patients, it's really going to be transformative," Oxnard said. DiMarco, who hopes to participate in the study, said she learned her genetic subtype by seeking out specialists around the country. Almost by chance her biopsy was tested by a Boston surgeon for the ROS1 alteration, which in 2010 was just newly identified. The mutation makes DiMarco a candidate for a drug called crizotinib, sold under Pfizer's brand name Xalkori. DiMarco, who has undergone numerous rounds of chemotherapy and radiation, has not yet resorted to Xalkori because she and her doctors want to keep that in the arsenal to use only if and when it becomes necessary. So far her disease has been kept in check, and she's been off chemotherapy for 17 months while undergoing regular scanning. Lisa GoldmanAnother young patient, Lisa Goldman, a mother of two who lives in Mountain View, was diagnosed with lung cancer in January at age 40. The disease was found in both lungs and considered stage four. Like DiMarco, Goldman has tested positive for the ROS1 mutation and has also chosen to hold off on Xalkori after receiving other therapies in combination with traditional chemotherapies. "I have that in my back pocket to use next," she said, referring to thePfizer drug. Goldman, who may not be eligible for the study now that she's 41, said the stigma of lung cancer because of its connection to smoking causes her to hesitate about naming her disease and then assert she's never smoked. But she speaks out about having lung cancer because she says she has to. "People need to know this happens. I'm not a fan of smoking, but nobody deserves to get cancer," she said. "Smoking is a contributor to breast cancer and heart disease and other disease, but people don't ask you if you caused this yourself." Goldman's latest scan showed her tumors had shrunk or remained stable, with the exception of one tiny new spot. But she tries to retain a sense of normalcy, particularly for her kids, ages 8 and 11. "How do you live with something like this hanging over your head?" she said. "You just can't live like every day is your last." Living in the present. DiMarco manages by incorporating Chinese medicine - acupuncture, massage, cupping therapy - into her life. As far as her young children know, their mom has some "bad cells in her body" that "made a spot in her lung" and that she has to take medications to get rid of it. While DiMarco knows she's been dealt a difficult hand, she tries to live in the present but look to the future about the potential treatment options. "It's all about what card you play that buys you the most time," DiMarco said. "If I understand what to do now ... I can sleep easier and not have to worry. But I need to have a plan. I need to know, what do we do next?" About lung cancer:

5/19/2014 Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation and Van Auken Private Foundation Announce the 2014 Young Innovators Team Award for Lung Cancer ResearchRead NowAward will fund teams of young, brilliant thinkers for research focused on immediate impact on lung cancer patient lives SAN CARLOS, CALIF. — The Bonnie J Addario Lung Cancer Foundation (ALCF), in collaboration with the Van Auken Private Foundation today announced the 2014 Young Innovators Team Award (YITA), a first-of-its-kind program that will fund and support teams of young investigators to conduct novel, innovative and transdisciplinary research with a potential of high clinical impact for lung cancer patients.

“In an effort to involve all stakeholders in our mission of making lung cancer a chronically managed disease by 2023, our goal with this program is to identify young, brilliant and collaborative out-of-the-box thinkers to deliver meaningful and measurable results in the field of lung cancer,” said Bonnie J. Addario, lung cancer survivor and founder of the ALCF. The 2014 Young Innovator Team Award, with funding from both the Addario Lung Cancer Foundation and the Van Auken Private Foundation, will provide up to a total of $500,000 per team over a duration of 2-3 years, to teams of two or more young investigators – those within five years of their first faculty appointment (www.lungcancerfoundation.org/grants). All submissions will be evaluated on the following four main criteria; that the proposed research be:

“Not only is lung cancer the least funded cancer, proportionate to the amount of lives it claims,” said Tony Addario, CEO of the Addario Lung Cancer Medical Institute (ALCMI), the ALCF’s sister organization and an international research consortium, “but it attracts disproportionately fewer young, talented thinkers because there is such a lack of funding for research. We hope this award is the first step in changing that. We also want to encourage young innovators to work together and collaborate in a transdisciplinary fashion focused on solving lung cancer patients’ pressing unmet medical needs.” The funding mechanism is designed in such a way that young investigators work together in cross-disciplinary teams and drive the projects, with guidance from mentors at their own institution, as well as the 2014 YITA Scientific Review Committee that will guide and steer their progress, and make final decisions on continued funding. “The idea is to encourage new thinking and foster leadership skills among young innovators, instilling confidence in them to drive breakthrough, transdisciplinary science under a collaborative, cross-institutional paradigm,” said David Carbone, M.D., Ph.D. at The Ohio State University, and one of the ALCF Scientific Review Committee members. The 2014 YITA Scientific Review Committee is comprised of four top global experts in the lung cancer field: David Carbone, M.D., Ph.D (The Ohio State University), David Gandara, M.D. (University of California, Davis), Roy Herbst, M.D., Ph.D (Yale School of Medicine), Giorgio Scagliotti, M.D., Ph.D. (University of Torino). ALCF invites lung cancer patient-oriented research in the following topic areas preferably (however, all submissions will be evaluated):

Key Dates: RFA Announcement: May 19, 2014

For more information on the award, guidelines for submission, FAQs and the online submission portal please visit www.lungcancerfoundation.org/grants. The Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation will accept online applications during June 3-August 1, 2014. Contact: Guneet Walia, Ph.D. Director, Research and Medical Affairs Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation 1100 Industrial Road, #1 San Carlos, CA 94070 [email protected] Funding for this unique new award is provided by the Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation and the Van Auken Private Foundation. About the Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation The Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation is one of the largest philanthropies (patient-founded, patient-focused, and patient-driven) devoted exclusively to eradicating Lung Cancer through research, education, early detection, genetic testing, drug discovery and patient-focused outcomes. The Foundation’s commitment to lung cancer patients is to collaborate and partner with the leaders in oncology, technology, science, medicine and philanthropy to make Lung Cancer a chronically managed disease by 2023. The Foundation works with a diverse group of physicians, organizations, industry partners, individuals, survivors, and their families to identify solutions and make timely and meaningful change. ALCF was established on March 1, 2006 as a 501c(3) non-profit organization and has raised more than $10 million for lung cancer research. To learn more, please visit www.lungcancerfoundation.org. About the Van Auken Private Foundation The Van Auken Private Foundation was established on April 17, 2008 as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. Its purpose is to make contributions, grants and provide assistance to other tax-exempt charitable organizations, in arts, science, medicine, education and worthy social causes. Sonia Williams of Spotlite Radio interviews President and CEO of The Joan Gaeta Lunt Cancer Fund, Joe Gaeta. From April 15th, 2014.

INHERIT EGFR Study Expands to Second Site SAN CARLOS, Calif., Oct. 30, 2013 /PRNewswire-USNewswire/ -- A new research study, funded by the Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation (ALCF), is aiming to understand how an inherited gene in some lung cancer patients could serve as an early detection screening for family members. "We're hoping this study provides new insight for methods to screen for lung cancer in people who might not have otherwise qualified for screening: the family members of lung cancer patients," said Bonnie J. Addario, lung cancer survivor and founder of the ALCF. "And we also hope to show that lung cancer doesn't just affect people who smoke." The INHERIT (Investigating Hereditary Risk from T790M) research study, facilitated by the Addario Lung Cancer Medical Institute (ALCMI), is the first to apply inherited familial genetics – widely used to assess risk for breast and colon cancer – to provide insight into lung cancer. Dr. Geoffrey Oxnard and a team of physicians at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women's Cancer Center in Boston, MA are leading the INHERIT study to understand whether the presence of the T790M gene mutation in lung cancers is associated with an inherited gene alteration. Oxnard's team will also examine whether having the inherited form of T790M raises the risk of lung cancer in patients and families. The ALCMI study was launched at Dana-Farber and has now expanded to include Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center in Nashville, Tenn. No travel is required to participate. "This is the first time we are using cancer genetics to offer insight into inherited familial genetics. For breast cancer or colon cancer, it is patients with a family history that get evaluated for inherited mutations in cancer risk genes," said Geoffrey Oxnard, MD, the lead researcher on the study. "For lung cancer, we propose that it is patients with specific genetic subtypes of lung cancer, those carrying the EGFR T790M mutation, that need to be evaluated for an inherited mutation in their family." Ultimately, the study aims to identify individuals and families who may have an increased risk of developing lung cancer so they can work with their physicians to reduce and manage that risk. Understanding lung cancer's underlying biology in high-risk families could also provide unique insight into why the disease develops and determine whether "germline" (inherited) factors may partly explain lung cancer in individuals without apparent carcinogenic association. "We are funding this study because of our patient first commitment," Addario said, "and with the hope to raise awareness that the risk for lung cancer exists regardless of smoking history. In 2013 alone, 34,000 people who never smoked will be diagnosed with lung cancer. That population of cancer patients, isolated, would represent the seventh leading cancer in the U.S." The INHERIT study is offered through Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, and soon at other ALCMI member institutions in the United States and Europe. It is led by Geoffrey Oxnard, MD at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women's Cancer Center. Dana-Farber and Vanderbilt are National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers. This study is also funded by the Conquer Cancer Foundation of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). FOR MORE INFORMATION: View video on T790 mutation research at www.dana-farber.org/T790Mstudy Contact Dr. Oxnard at 617-632-6049, [email protected] About the Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation The Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation (ALCF) is one of the largest philanthropies (patient-founded, patient-focused, and patient-driven) devoted exclusively to eradicating Lung Cancer through research, early detection, education, and treatment. The Foundation works with a diverse group of physicians, organizations, industry partners, individuals, survivors, and their families to identify solutions and make timely and meaningful change. The ALCF was established on March 1, 2006 as a 501c(3) non-profit organization and has raised more than $10 million for lung cancer research and patient services. About the Addario Lung Cancer Medical Institute The Addario Lung Cancer Medical Institute (ALCMI) is a patient-founded, patient-focused 501c(3) non-profit research consortium established in 2008 that directly facilitates basic and clinical research to accelerate the discovery and delivery of advancements to patients. By bringing together a world-class team of scientists and clinicians from over 20 academic and community medical centers in the U.S. and Europe, ALCMI has rapidly established a critical mass of expertise and dedicated research infrastructures linked together through centrally coordinated research. SOURCE Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation Read more: http://www.digitaljournal.com/pr/1556776#ixzz2jK46ND7q The following article was originally published in LSF Magazine: Fall 2012. Copyright 2012 Life Sciences Foundation. In Part I, we recounted how former oil executive Bonnie J. Addario survived lung cancer and embraced a new calling: patient activism. She started the Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation (BJALCF) with two goals: 1) to raise public awareness about the relative neglect of lung cancer in biomedical research, and 2) to help lung cancer patients navigate effectively through the healthcare system toward the best available care.

Addario soon realized the necessity of a third goal: to enlist the aid of physicians and biomedical scientists in the reorganization of cancer research. In November 2007, she convened the first annual BJALCF Lung Cancer Summit in San Francisco, and posed a simple question to an audience of prominent oncologists: “If money were no object, what would you do to increase lung cancer survival rates?” Tissue is the issue Dr. Harvey Pass, Director of the NYU Division of Thoracic Oncology, stood to respond: “We need a bio-repository operated by an honest broker, and collaborative agreements to ensure that institutions donate tissues.” The fight against cancer in the emerging era of genomics and personalized medicine depends crucially on the identification of tumor biomarkers – mutated genes or molecules associated with the development of specific types of malignancies. Biopsied tissues are basic raw materials that researchers need to develop improved diagnostic tests and targeted therapies. As Bonnie puts it, sample collection is “a search for gold.” The value of biomarkers in the development of diagnostic tests and therapies has been amply demonstrated. In the case of lung cancer, for example, a genetic test is now available to detect a specific mutation in the gene that codes for a protein called epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). The mutation causes overexpression of the protein, which leads to aggressive forms of lung cancer (and colorectal, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers as well), tumors that readily metastasize and are resistant to standard chemotherapies. For lung cancer patients who carry the mutation, the best available drug is Genentech’s Tarceva®. Tarceva targets EGFR and inhibits its biological action. “Think about it this way,” says Bonnie. “A carpenter would never leave the house without a full toolbox – a hammer, a screwdriver, a saw, and so on. Molecular analysis of tissues is the tool that oncologists need to select the right treatment for the unique patients sitting in front of them.” Oncologists have long collected and analyzed tissue samples in order to characterize, predict, and monitor the progression of tumors. It was never common, however, to share samples broadly. With limited tools and techniques for the investigation of cancer genetics and scarce understanding of the heterogeneity of cancer as disease category, demand was limited. Specimens were regularly discarded after testing. Now, however, genomics technologies permit far greater differentiation in tumor typing. Demand for specimens is growing. Comprehensive identification of mutations and gene expression patterns implicated in oncogenesis will require genomic analysis of large sets of tissue samples. Boom and bust In the early 1990s, there were great expectations among genome scientists, entrepreneurs, investors, and drug companies that the identification of genetic markers would streamline drug discovery and development and form the basis of a new sector of the pharmaceutical industry. A large cohort of companies appeared, ready to implement genomics technologies in drug target screening, identification, and validation, but the data licensing business model adopted by most firms proved unsustainable. Information alone doesn’t make a drug. Drug design involves making safe and effective interventions in strictly regulated and finely tuned biochemical signaling pathways nested in highly complex biological systems. A lot can go wrong. Even if a pharmaceutical company possesses a promising target, there is no guarantee that it will be able to develop an efficacious drug. Most attempts fail. If all goes well in the laboratory and clinical testing – a very rare course of events – then one might expect a drug in perhaps ten years at a cost of half a billion dollars. Given the length, expense, and uncertainty of the drug development process, pharmaceutical companies questioned the value of biomarkers. What is a fair price? Eventually, the answer became clear: not enough in many cases to support the commercialization of biomarkers as a main line of business. After pharmaceutical houses had made a first pass and selected priority drug development targets, demand for biomarkers slackened. Firms licensing gene sequences struggled to remain profitable. Many genomics companies elected to divert resources to the downstream development of diagnostic products or drugs. Oncologists had anticipated an avalanche of cancer biomarker data, but only a trickle arrived. Academic labs carried on the study of cancer genomics, but with fewer resources, and in a mostly uncoordinated manner. The advent of genomics has increased demand for tissue specimens by several orders of magnitude, yet competition in science has continued to put pressure on academic laboratories to generate data and publications independently rather than cooperatively. There have been few concerted efforts to pool genomics data in cancer research. There is no central repository. When Bonnie Addario surveyed the institutional landscape, she saw a case market failure. She was enthusiastic about the promise of genomics for the development of individualized treatments and improved outcomes for lung cancer patients, but frustrated by the organizational and economic impediments to translation of biomedical advances from ‘bench to bedside.’ Attendees at the BJALCF Lung Cancer Summit agreed that patients would benefit from changes in the way cancer biomarker data are generated and disseminated. Storming the silos After the meeting, Bonnie assembled a team to organize the proposed clearinghouse. Joining her as president of the Addario Lung Cancer Medical Institute (ALCMI – pronounced ‘alchemy’) were Steven Young, former Executive Director of the Multiple Myeloma Research Consortium, and a core group of leading oncologists, thoracic surgeons, and laboratory scientists – Harvey Pass from NYU Langone Medical Center, David Carbone of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, David Gandara, from University of California-Davis School of Medicine, David Jablons, from the University of California, San Francisco, Pasi Jänne from Harvard Medical School and the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Ite Laird-Offringa of the University of Southern California, Rafael Rosell from the Catalan Institute of Oncology in Spain and Giorgio Scagliotti from the University of Torino. “These were really the top guys in the business,” says Young, who was appointed President of the organization. As the only non-scientist on the board, Bonnie represented the patient perspective. “I insisted that she have veto power,” says Young, “to make sure that our mission wasn’t hijacked.” Addario was gearing up to wage “a battle against the status quo.” She had selected a board that she believed was willing to reform established institutional processes in biomedical research. The group formulated goals, established ground rules, and developed a unique operational model. ALCMI was established to break down barriers. Bonnie intended the group to serve as a virtual mediator that would 1) establish connections and facilitate communication between ‘research silos’ (academic and industrial laboratories reluctant to collaborate and share information); 2) link and standardize existing biobanks in a cooperative network; and 3) provide an information technology infrastructure for the broad and efficient dispersion of data across the institutional topography of the global cancer research establishment. The initial goal, agreed upon at the first meeting of the ALCMI board, was to affect the clinical management of lung cancer in a significant way within three years. The timetable was ambitious. It reflected Bonnie’s “no-nonsense” business approach to leading the consortium. The cancer survivor and former oil company executive had little patience with the established conventions of academic life. “A lot of people were doing good things in cancer research,” she says, “but didn’t fully understand the need to shake up the academic system. We’re running ALCMI as a business. We don’t sit around and create ideas and not implement them. We make sure they happen and we measure what we’re doing. We operate using business principles.” Fourteen academic universities and community hospitals have joined formally as collaborators. In the United States, participating institutions include the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, the Hoag Memorial Hospital Presbyterian in Newport Beach, California, the Lahey Clinic in Burlington, Massachusetts, New York University, the University of California, Davis, the University of California, San Francisco, the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, Alta Bates Summit Medical Center in Oakland, Palo Alto Medical Foundation in Palo Alto, Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, and Memorial Cancer Institute in Hollywood, Florida. Abroad, ALCMI enrolled programs at the Catalan Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, Spain, the Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France, and the University of Torino in Turin, Italy. Four additional medical centers in the U.S. have been invited to join ALCMI, bringing the total number of community hospitals to eight— ALCMI is unique in engaging community-based clinicians and community hospitals in translational research. Despite the urgency of her mission, Bonnie understood that laboratory research moves forward according to its own timetable. Advancing basic science takes time, money, and luck. Breakthroughs can’t be predicted. They can’t be planned. Bonnie believed, however, that promising findings too often circulate for extended periods through restricted academic channels in which interests in publication and tenure take precedence over the translation of research to medical applications. Bonnie and company planned to operate differently. Steven Young says, “ALCMI is not a private playground for scientists in the consortium. We stated that clearly to our academic partners. We said, ‘We’re not trying to continue what you normally do. We’re creating this resource so that scientists around the world can access it.’” As new member organizations joined and coordination challenges arose, ALCMI evolved into a contractual consortium. In order to gain access to the organization’s bio-repository resources, participating institutions must agree to adhere to non-negotiable policies on control of data and intellectual properties, tissue collection and usage, and revenue sharing. These contractual agreements obviate the need to negotiate separate deals with multiple technology transfer offices. They streamline the process of involving new institutional participants and contributors. The goal is effective collaboration with far less red tape. Through the contract system, ALCMI has been able to re-route flows of information in academic collaborations – investigators and research institutions have evidently recognized the sense and value in ALCMI’s innovative methods. ALCMI is not the only non-profit organization working to share tissue samples and disseminate biomarker data, but similar groups are few in number. According to Steven Young, “there are only three or four of these around the world. It takes a lot of nerve and a lot of money.” ALCMI is currently the only group dedicated exclusively to the acceleration of lung cancer research. Remove the bricks, remove the mortar, disseminate the research Two years ago, ALCMI expanded its bold experiment to include the analysis of tissue and plasma samples. The organization initiated the CASTLE Network Study (Collaborative Advanced Stage Tissue Lung Cancer Network), a networked research project that performs laboratory testing on tumor specimens donated by lung cancer patients. The structure is simple. Late-stage cancer patients provide tissue and blood samples at one of seven participating institutions nationwide. Clinicians perform molecular tests to identify biomarkers that might provide clues about the future behavior of the cancer. The samples remain in the bio-repository as a resource for researchers worldwide; test results are sent to the patient’s doctor to help determine the best course of treatment. The CASTLE study is the beginning of a move toward improved, personalized treatment plans for lung cancer patients. Participating physician and ALCMI board member David Carbone explains that information provided by the institute “enables physicians to make informed decisions on best available treatments – it often allows them to make earlier therapeutic interventions and to prescribe highly effective, targeted drugs rather than nonspecific and toxic chemotherapies.” CASTLE study findings also help researchers identify new biomarkers and learn more about the genetic preconditions, cascading biochemical pathways, and cellular dysfunctions that characterize cancers in lung tissues. Research is moving ahead. In April 2011, Biodesix, a molecular diagnostics company located in Broomfield, Colorado, a Denver suburb, began testing tissue samples collected from late-stage cancer patients enrolled in the CASTLE study with a serum proteomics test called VeriStrat®. In January 2012, researchers at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), with support provided by the BJALCF, developed a similar molecular test in hopes of accurately predicting the future behavior of lung tumors. Parallel drug testing projects are underway with support from the BJALCF. In 2010, Dr. David Gandara, a member of ALCMI’s Scientific Board, and a special advisor for experimental therapeutics at the University of California, Davis (UCD) Cancer Center, began collaborating with Jackson Laboratory-West and the National Cancer Institute Center for Advanced Preclinical Research to test the effects of varied drug regimens against specific tumors. Malignant cells from lung cancer patients receiving treatment at UCD have been engrafted onto multiple mouse models and tested serially for positive responses to newly-developed anti-cancer therapies. The goal, Gandara says, is to identify the specific lung cancer mutations that are most common, and most treatable: “There are at least 150 different types of lung cancer, so every patient a physician sees is going to be a little different. We need to find, say, the five or six characteristics that are shared by all the cancers – the most common mechanisms. That’s where we should focus treatment.” The BJALCF began funding Gandara’s research in 2010. A recent progress report revealed that mice engrafted with variations of the EGFR mutant tumor model showed virtually complete reductions in tumor size when treated with afatinib, a drug being tested by Boehringer Ingelheim for patients with EGFR mutation positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), in combination with cetuximab (Erbitux®), a monoclonal antibody marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Eli Lilly and Company that targets EGFR receptors. Clinical trials of the experimental combination therapy in human beings are underway, after the encouraging preliminary results in animal testing. Developing alternative treatment options also requires enrolling more patients in clinical trials. Pharmaceutical companies often struggle with recruitment. Fewer than 5 percent of lung cancer patients participate in tests of experimental therapies. As a former patient, Bonnie understands their reluctance: “Most people think of clinical trials as a last resort. They think it signals the end of the road.” For many people with cancer, entering a clinical trial marks a passage in status, from patient receiving care to doomed guinea pig. She has firsthand experience with the phenomenon. When her cousin was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, the doctor recommended a clinical trial. At her cousin’s next appointment, a trial representative walked into the physician’s office wearing a suit and carrying a briefcase full of enrollment paperwork detailing risks. The reaction from Bonnie’s cousin was immediate and powerful: “No way.” Bonnie is mobilizing the BJALCF to develop more effective enrollment techniques: “I tell patients that at one point, Tarceva was in a trial, and that the people who took it lived longer. We can get patients into clinical trials, but we need to educate them. We have to explain what trials are all about, and tell how genomics is enabling the invention of better medicines.” Her message is that clinical trials give patients the best chance for survival. As Steven Young indicates, the BJALCF’s patient recruitment effort is an important piece of the virtual network: “BJALCF can get access to the patients, ALCMI has access to the scientists, and we have established an infrastructure to support the research. Our contracts, our data systems, our processes for doing correlative science studies are changing lung cancer research and care.” Lung cancer education In 2012, the BJALCF and ALCMI have launched further initiatives to inform and empower patients and enlist the aid of healthcare professionals. Working collaboratively with GE Healthcare Oncology Solutions, BJALCF is developing the Patient 360 program. A pilot version has been introduced at El Camino Hospital in Mountain View, California, under the direction of Dr. Shane Dormady. The BJALCF is also compiling a “360 Degree Patient Handbook” for patients, their families, and health care providers. The handbook is a goldmine of information covering all aspects of the lung cancer experience including diagnosis, cancer staging, targeted treatments, and clinical trials. Bonnie recalls her own firsthand introduction to the world of oncology: “Everyone kept saying that cancer is a journey, but no one could provide me with a roadmap. This handbook is the culmination of years of research, conversations with lung cancer experts and patients, and my personal experience.” A free iPhone app will alert patients of new discoveries and breakthroughs in lung cancer research. Bonnie insists that the best patient advocates are educated patients themselves. The BJALCF is working hard to encourage and enable informed, proactive participation by patients and families in cancer care: “We want to teach the patient what to ask for from the very beginning of the long hard road on which they will travel. When the doctor says, ‘You have a metastasis to the brain, you need radiation,’ they will have the background knowledge to reply, ‘Well, are we considering whole brain radiation, gamma knife, or cyber knife procedures?’ They will be able to personalize their treatment and demand a seat at the table.” Before patients demand a seat at the table, they are offered a space on a couch at the BJALCF Lung Cancer Living Room support group. The Living Room is an open forum for patients and their families to voice questions and concerns, share lessons learned, and hear from experts in the field of lung cancer research and medicine. Recently, Living Room conversations debuted on the worldwide web. “We are now live streaming into patient’s homes,” Bonnie reports. “It’s open to anyone who wants to dial in, and that includes the pharmaceutical industry. We are not restricting access. We are not keeping anyone out.” These patient-focused programs are part of a larger campaign by the BJALCF and ALCMI to reshape the institutional foundations of cancer care. Efforts to create more knowledgeable, more responsive, and better equipped community hospitals are another important part of the process. Seventy to eighty percent of all cancer patients are treated at community hospitals, but molecular testing is far from a widespread or standard procedure, and many patients do not learn about the latest treatment options. “Patients are getting the same old, same old,” says Bonnie. “Whatever the oncologist was giving them before, that’s what they’re kept on.” BJALCF is spearheading a community hospital referral program. The program is designed to provide community hospitals with incentives to improve, to acquire the tools and forms of expertise required to diagnose and treat cancers based on the results of personalized molecular testing. And if superior resources or specialists are to be found elsewhere, the BJALCF will refer patients out to complete their treatment at different hospitals. “The tissue under the microscope” Bonnie J. Addario has extended patient activism to the formation of a virtual research network that links cancer patients, oncologists, biomedical researchers, and pharmaceutical companies in order to realize the potential of cancer genomics and personalized medicine. She is attempting to tear down institutional walls and push scientific and medical experts to work smarter and more cooperatively in order to save more lives. Her message to researchers, physicians, and industry leaders is that their work is profoundly important to cancer patients and their friends and families – never forget it! The tissue under the microscope, she reminds them, came from a human being who desires to live: “When you go back to your labs, remember that you’re not just looking at cancer cells. You’re looking at a patient. This person has given you their tissues, their cells, to help you advance lung cancer care.” “We’re in the phase now,” says Bonnie, “where we have identified a genetic mutation or bio-marker for something like thirty or forty percent of lung cancers. Many of them we can treat.” The mission shared by the BJALCF and ALCMI is to identify the other sixty percent and make sure that patients know about it. Bonnie sums up the project: “We partner and collaborate with academic institutions, pharma corporations, and biotech firms. We take our most prized possessions and share them in order to speed the delivery of life-saving medical products to patients. We have to do it.” Reflecting on her life and luck, Bonnie says, “When I became President of Olympian Oil, someone said to me, ‘You’re really lucky.’ I thought, ‘Me? Lucky?’ But then I realized I was lucky. I loved what I did every day. But I also realized that I hadn’t been called to do it. I didn’t know what I was meant to do, but I knew my job at Olympian wasn’t it. Now I know. This is it. What more can we do, what better footprint can we leave, than to say ‘I saved a life?’ Even if it’s just one, that’s pretty good.” |

Details

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed