|

Mortality

Incidence

Survival

Causes and Costs

SOURCES

0 Comments

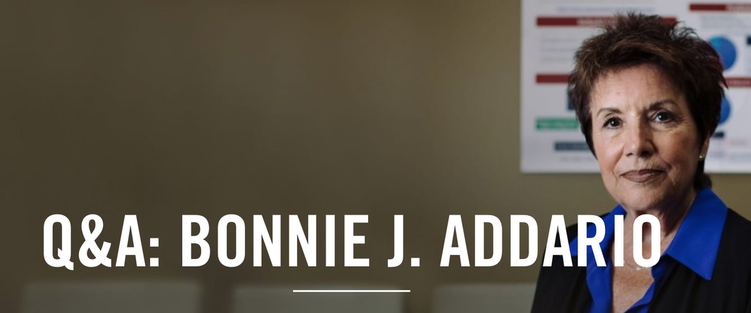

We cannot think of a better way to kick of Lung Cancer Awareness Month 2016 than with this excellent Q&A with a leader in the movement - and our friend - Bonnie Addario. Please read this inspirational and informative interview from Genentech: https://www.gene.com/stories/qa-bonnie-j-addario

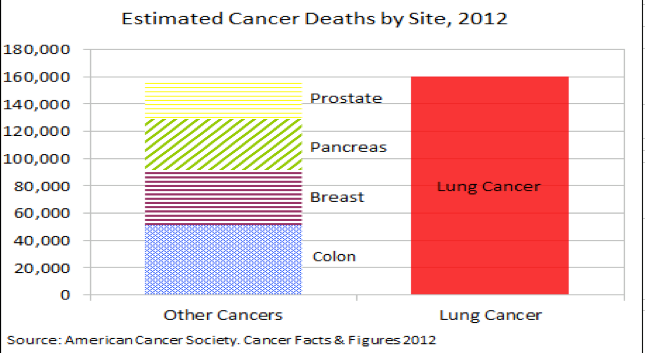

by Lynne Eldridge MD. Originally posted on 30 October 2015 at About.com. Many of us have been upset recently as well-meaning organizations have made smoking cessation the focus of lung cancer awareness month. Certainly, encouraging the public to never begin, and to quit if they smoke, is admirable. And for people with lung cancer, quitting may improve survival. Yet lung cancer awareness month should have a different focus. Spreading information on smoking cessation does little overall for those living with lung cancer today. Five months after receiving a diagnosis of lung cancer, only 14% of people with the disease are smokers. To focus on smoking is analogous to making breast cancer awareness month all about informing women that they should have their first child before the age of 30 (to decrease the risk of breast cancer.) Awareness month should be about supporting people with the disease, not about discussing the causes. Awareness month should also be about funding to research better treatments. Those who smoked in the past won't benefit from a lecture about what they may have done differently 20 years ago. Instead, they need treatment today. And for never smokers with the disease--not uncommon considering lung cancer in never smokers is the 6th leading cause of cancer deaths in the U.S.--this focus makes a month designed to celebrate their lives irrelevant. Some people may remain skeptical, but read on for further reasons why lung cancer awareness month should not have smoking cessation as the central focus. The majority of people with lung cancer are non-smokers. This heading is not a typo. The majority—roughly 60% of people—diagnosed with lung cancer are non-smokers. This includes people who smoked at some time in the past, as well as never smokers. In the United States 20% of women with lung cancer are never smokers, with that number rising to 50% of women with lung cancer worldwide. Numbers such as 20% may seem small, until you take a look at the statistics. Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths in both men and women in the United States. Lung cancer kills twice as many women as breast cancer, and 3 times as many men as prostate cancer. And while around 30 to 40% of people smoke at the time of diagnosis, only 14% of people with lung cancer are smoking 5 months after diagnosis. In other words, the vast majority of people with lung cancer today will not benefit from hearing about the hazards of smoking. Not only is this focus not helpful, but it serves to propagate the stigma of lung cancer as a smoker's disease. Unfortunately this vast majority, including most never smokers, have already been subjected to the blame game. Have breast cancer? Nice. People act loving and ask how they can help you. Have lung cancer? Raised eyebrows accompanied by some variation of the question,"How long did you smoke?" There are many reasons that living with lung cancer can be harder than living with breast cancer. Let's not add cancer awareness month to the list. There are Other Causes of Lung Cancer There are many causes of lung cancer. Even if tobacco had never been introduced on the planet, we would still have lung cancer. Yes, smoking is the leading cause of lung cancer, but causes other than smoking are very important. Though the number seems small—20% of women who develop lung cancer being never smokers—this translates to a fifth of the 71,660 lung cancer deaths in women expected for 2015. Radon exposure in the home is the second leading cause of lung cancer, and the number one cause of lung cancer in non-smokers. Roughly 21,000 people die from radon-induced lung cancer each year, and this cause is entirely preventable. Picking up a radon test kit from the hardware store for around 10 bucks, and having radon mitigation done if the test is abnormal, is all that's needed. Putting these numbers in perspective may help. Around 39,000 women are expected to die from breast cancer in 2015. If we had a $10 test to check for a risk factor, and a procedure costing less than a grand that could completely prevent half of breast cancer deaths, do you think we would have heard? Why doesn't the public know about this? It goes back to the focus of this article; we are placing the emphasis of lung cancer awareness on smoking, and in doing so, are leaving the public with a false sense of assurance that all's well if you don't smoke. There are other causes worth mentioning, from air pollution, to indoor air pollution, to secondhand smoke, to occupational hazards. Don't assume you are safe if you never smoked. Learn about the other causes of lung cancer in non-smokers and what you can do to reduce your risk. People Who Have Quit Smoking Are Still at Risk Quitting smoking certainly reduces the risk of lung cancer, but for most, some risk always remains. The numbers in the last slide attest to this. There are more former smokers who develop lung cancer each year than current smokers. If you smoked in the past, don't fret yet. After 10 years of quitting, the risk of lung cancer decreases by 30 to 50%. There are also some ways of reducing your risk of dying from lung cancer. One method is low dose CT lung cancer screening. While screening doesn't lower the chance that you will get lung cancer, it does increase the chance that if you develop lung cancer, it will be found in the earlier, more curable stages of the disease. It's thought that screening people at risk could reduce the mortality rate from lung cancer by 20% in the United States. Screening is currently recommended for people between the ages of 55 and 80, who have a 30 pack-year history of smoking, and continue to smoke or quit within the past 15 years. In some cases screening may be recommended for other people based on personal risk factors for lung cancer. In addition, studies looking at exercise and lung cancer as well as diet and lung cancer suggest there are some things that both people without and people with lung cancer can do to lessen risks. The Stigma Interferes With Early Diagnosis My favorite part of lung cancer events I attend, is when lung cancer survivors share their story. A special time, but oh so painful. Time and time again people share what eventually led to their diagnosis -- often a series of visits, with several doctors, over a period of months, during which time they have been diagnosed with everything from asthma to Lyme disease. Lung cancer flies below the radar screen for many health care professionals, especially lung cancer in never smokers and lung cancer in young adults. For this reason, many are diagnosed when lung cancer has already spread, and the chance of a cure with surgery has passed. In fact, young adults and never smokers are more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage of the disease. Until we have a widespread screening tool for lung cancer, it's important for health professionals and patients alike, to realize that all you need to get lung cancer is lungs. The symptoms of lung cancer can be different in non-smokers than smokers, and those of lung cancer in women are often different than symptoms in men. Be your own advocate. If you have any symptoms that aren't adequately explained, ask for a better explanation or a second opinion. If we are to find lung cancer early, we need to dispel the myth that lung cancer is a smoker's disease. That's part of what lung cancer awareness month is all about. The Stigma Interferes With Research for New Treatments Private funding for breast cancer surpasses that of lung cancer by a great distance, as evidenced by Susan G. Komen being a household word and pink ribbons having a widely recognized significance. How many people can name the largest non-profits for lung cancer, and how many people even know the color of the lung cancer ribbon? Public funding also lags far behind for lung cancer, and this is important because funding means dollars which in turn means research. In 2012, federal research spending added up to $26,398 per life lost to breast cancer, vs only $1,442 per life lost from lung cancer. I have often wondered what the survival rate for lung cancer would be if the same amount of money and research had been invested as has been with breast cancer. Why is the funding so low, and why are researchers less likely to devote themselves to lung cancer? The stigma. There is an unseen, unheard statement that says, "These people smoked so they deserve to have cancer." Nobody deserves to have lung cancer, whether a never smoker or a lifelong smoker. Making smoking cessation the focus of lung cancer awareness only increases this stigma and gap. The Stigma Interferes With Research About Causes I made a comparison earlier about deaths from breast cancer, vs that from radon-induced lung cancer. That can be taken a step further. I read studies galore looking at possible causes of breast cancer, as well as dietary and other measures which may reduce the risk. It's rare when I find similar studies looking at lung cancer. What is causing lung cancer in non-smokers? Why is lung cancer increasing in young, never smoking women? We need to change the face of lung cancer, so that we can begin to look at possible answers to these questions. Lung Cancer is Increasing in Young, Never-Smoking Women Most of us have read the headlines in recent years. Lung cancer in men is now decreasing in the United States, while that in women has leveled off. Yet there is one group for whom lung cancer is steadily increasing. Young, never-smoking women. These women have to put up with constant questions about their smoking status, or another variant, "Did your parents smoke when you were growing up?" Why can't we treat these women as we treat women with breast cancer in October? Lung cancer isn't a "smoker's disease." Someone with lung cancer could be your mother or your daughter or your sister or your aunt. These young women deserve to know that they aren't being dismissed for having a smoker's disease, while at the same time coping with the stigma. Focus of Lung Cancer Awareness Month Okay. So smoking cessation shouldn't be the focus of lung cancer awareness month. What should be at the center of awareness? Number one should be support. Every single person with lung cancer -- regardless of smoking history -- deserves our love, compassion, and the best care possible. Think of how women are treated during breast cancer awareness month, how they are celebrated, how they are reminded that research is being done to make a difference. If you just don't know what to say, check out these tips on things not to say to someone with lung cancer. How would you treat your friend or loved one with lung cancer differently, if she had breast cancer instead? Number two should be about awareness. Not smoking cessation as this is done everywhere year round. Instead awareness that lung cancer occurs in non-smokers and having knowledge of the early symptoms could make a difference. Those who are former smokers should have the opportunity to learn about screening options. And just as breast cancer awareness month raises funds for research, lung cancer awareness month should also be a time to educate and encourage those with lung cancer about new advances, while providing funding for further advances. A Word About Smoking and Lung Cancer For smokers with lung cancer, quitting is critical. To speak of separating lung cancer awareness month from smoking is not to dismiss smoking as a cause of lung cancer. It is. For the minority of people living with lung cancer who smoke, quitting is incredibly important, and likely the most important thing anyone can do to improve survival. Check out these 10 reasons to quit smoking after a diagnosis of cancer. Quitting smoking after a diagnosis of lung cancer improves the response to cancer treatments, improves quality of life, and improves survival. For those without lung cancer, quitting not only reduces lung cancer risk, but improves survival in other ways. In addition to lung cancer, there are many cancers that are associated with smoking, and many other medical conditions associated with smoking. The Quit Smoking Toolbox is a free resource to help you gather the tools you need to be successful in giving up the habit. But remember that these tips on smoking and cancer were placed at the end for a reason. They apply to only a minority of people living with lung cancer today. Sources:

Amato, D. et al. Tobacco Cessation May Improve Lung Cancer Patient Survival. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2015. 10(7):1014-9. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. Accessed 06/08/15. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@editorial/documents/document/acspc-044552.pdf American Society of Clinical Oncology. Cancer.net Tobacco Use During Cancer Treatment. 04/2012. http://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/prevention-and-healthy-living/tobacco-use/tobacco-use-during-cancer-treatment Amato, D. et al. Tobacco Cessation May Improve Lung Cancer Patient Survival. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2015. 10(7):1014-9. Howlader, N., Noone, A., Krapcho, M., Garshell, J., Miller, D., Altekruse, S., Kosary, C., Yu, M., Ruhl, J., Tatalovich, Z., Mariotto, A., Lewis, D., Chen, H., Feuer, E., and A. Cronin (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, based on November 2014 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2015. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/ National Cancer Institute. Cancer Statistics. Accessed 06/08/15. http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/what-is-cancer/statistics National Cancer Institute. Lung Cancer Prevention (PDQ). Updated 05/12/15. http://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/patient/lung-prevention-pdq#section/_12 National Cancer Institute. Smoking in Cancer Care—for Health Care Professionals. Accessed 08/01/15. http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/tobacco/smoking-cessation-hp-pdq#section/_1 Parsons, A. et al. Influence of smoking cessation after diagnosis of early-stage lung cancer on prognosis: systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. British Medical Journal BMJ2010:340:b5569. Published online 21 January 2010.

Originally published on June 24th, 2014 by Victoria Colliver at SFGate.com.

Victoria is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. --- Natalie DiMarco's only obvious risk factor for getting lung cancer was having lungs. Natalie DiMarcoDiMarco had been experiencing respiratory problems for months in 2010, but her doctors just assumed the mother of two had allergies. By the time she learned she had lung cancer, the disease had spread into her lymph nodes and reached the membranes that surround the lungs. "I'm young, didn't have any history of smoking, and that's why a doctor didn't X-ray me from the beginning," said DiMarco, now 36, who lives in Penngrove with her husband, daughters, ages 5 and 6, and a teenage stepson. An estimated 4,600 to 6,900 people under 40 in the U.S. are diagnosed every year with lung cancer that has no apparent cause. The disease appears to be quite different from the lung cancer found in longtime smokers and, aside from initial research that indicates that young patients, like DiMarco, tend to share certain genetic changes, the source remains a mystery. A new study just getting under way hopes to find out more about these patients, what they have in common and, potentially, why they get lung cancer. If researchers can find a common thread, or several, it could lead to more effective treatment or point the way to new targeted therapies. The $300,000 Genomics of Young Lung Cancer Study is small - just 60 patients - but the lead researchers hope it will help find the answers they're looking for and even help others with lung cancer, particularly the 15 percent of the nearly 230,000 Americans diagnosed with lung cancer each year who have never smoked. Addario Lung Cancer Medical Institute, a partner organization of theBonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation in San Carlos, initiated and is paying for the study along with Genentech. Not much is known. Bonnie Addario, who was diagnosed with lung cancer in her mid-50s in 2003 and founded the organizations that bear her name, said much is unknown about this population of patients because it's never been systematically studied. "We're hoping to find something that may be in another cancer or another disease that could be part of their therapy," she said. Dr. Barbara Gitlitz, a lead researcher of the study and director of the lung, head and neck program at theUniversity of Southern California's Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, said the disease should be thought about as its own entity. "We may discover that by looking at the genomics of these people, we may find driver mutations. We'll see patterns that might be specific to this population and we might see something new," she said. Time is of the essence, considering how devastating a lung cancer diagnosis is. Bonnie AddarioJust 15 percent of people diagnosed with lung cancer live longer than five years, in part because the disease is difficult to detect in its earlier stages and tends to be caught too late. That's particularly true among young people because no one's looking for it. "What we're hearing quite often is that they're athletes and they're very fit - the people you would least expect to have cancer, let alone lung cancer," Addario said. She added that the disease appears to be more common in young, nonsmoking women than in their male counterparts. Inspired by Cal athlete. Jill CostelloThe study was inspired by Jill Costello, a San Francisco native and varsity coxswain for UC Berkeley's women's crew, who died of lung cancer in 2010 at age 22, a year after she was diagnosed. Jill's Legacy, a subsidiary of Addario's foundation, was created in her honor to raise funds and awareness for lung cancer among young people. Researchers do know that young people and nonsmokers with non-small-cell lung cancer - the most common kind - typically have alterations in their genes that can affect how the disease is treated. The genetic mutation found most often - EGRF, for epidermal growth factor receptor - occurs in about 10 to 15 percent of non-small-cell lung cancer patients. But a host of other known mutations - ALK, ROS1, BRAF, HER2, MET, RET - have also been identified as contributing to lung cancer in young patients, said Dr. Geoffrey Oxnard, a lung cancer specialist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, also a lead researcher of the study. Drugs have been developed in recent years to "target" those mutations, or go after those specific cells to thwart their growth. The first EGRF therapies, AstraZeneca's Iressa, or gefitinib, was approved by federal regulators in 2003 followed by Roche's Tarceva, or erlotinib, in 2005. But even these relatively new treatments don't cure the disease; at most they buy time - from several months to five years - before the cancer returns. Oxnard said he hopes the study - which will test for more than 200 mutations - will not only show a pattern of these genetic alterations but also spotlight the necessity for young and nonsmoking people to get genetically tested after diagnosis, which is not routinely done in all centers. "We know comprehensive genetic testing has the potential to make a difference in any cancer patient, but we think in these patients, it's really going to be transformative," Oxnard said. DiMarco, who hopes to participate in the study, said she learned her genetic subtype by seeking out specialists around the country. Almost by chance her biopsy was tested by a Boston surgeon for the ROS1 alteration, which in 2010 was just newly identified. The mutation makes DiMarco a candidate for a drug called crizotinib, sold under Pfizer's brand name Xalkori. DiMarco, who has undergone numerous rounds of chemotherapy and radiation, has not yet resorted to Xalkori because she and her doctors want to keep that in the arsenal to use only if and when it becomes necessary. So far her disease has been kept in check, and she's been off chemotherapy for 17 months while undergoing regular scanning. Lisa GoldmanAnother young patient, Lisa Goldman, a mother of two who lives in Mountain View, was diagnosed with lung cancer in January at age 40. The disease was found in both lungs and considered stage four. Like DiMarco, Goldman has tested positive for the ROS1 mutation and has also chosen to hold off on Xalkori after receiving other therapies in combination with traditional chemotherapies. "I have that in my back pocket to use next," she said, referring to thePfizer drug. Goldman, who may not be eligible for the study now that she's 41, said the stigma of lung cancer because of its connection to smoking causes her to hesitate about naming her disease and then assert she's never smoked. But she speaks out about having lung cancer because she says she has to. "People need to know this happens. I'm not a fan of smoking, but nobody deserves to get cancer," she said. "Smoking is a contributor to breast cancer and heart disease and other disease, but people don't ask you if you caused this yourself." Goldman's latest scan showed her tumors had shrunk or remained stable, with the exception of one tiny new spot. But she tries to retain a sense of normalcy, particularly for her kids, ages 8 and 11. "How do you live with something like this hanging over your head?" she said. "You just can't live like every day is your last." Living in the present. DiMarco manages by incorporating Chinese medicine - acupuncture, massage, cupping therapy - into her life. As far as her young children know, their mom has some "bad cells in her body" that "made a spot in her lung" and that she has to take medications to get rid of it. While DiMarco knows she's been dealt a difficult hand, she tries to live in the present but look to the future about the potential treatment options. "It's all about what card you play that buys you the most time," DiMarco said. "If I understand what to do now ... I can sleep easier and not have to worry. But I need to have a plan. I need to know, what do we do next?" About lung cancer:

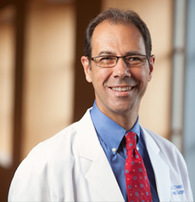

This article was originally published at 4:24 pm on Tuesday, December 3, 2013 by Kathryn Roethel of the San Francisco Chronicle When it comes to U.S. cancer research funding, deadly disease doesn't always translate into dollars. Lung cancer - the nation's top cancer killer - ranks near the bottom by many measures of funding. Lung cancer's five-year survival rates have hovered around 15 percent for the past four decades, while survival rates for most other cancers have climbed. Ninety-nine percent of prostate cancer patients and 89 percent of breast cancer patients now live at least five years past diagnosis. Lung cancer symptoms are vague and there isn't a screening approved for the general population, so doctors often discover lung cancer in advanced stages. Last year, the National Cancer Institute, a division of the government's National Institutes of Health, awarded breast cancer researchers nearly twice as much funding as lung cancer scientists. In the ratio of research dollars to deaths for the 10 most common types of cancer, lung cancer ranks near the bottom of the list. One problem, according to Dr. Heather Wakelee, a thoracic oncologist at the Stanford Cancer Institute, is that most people view lung cancer as a smoker's disease that could have been prevented. While a majority of U.S. lung cancer patients are current or former smokers, about 20 percent of women and 10 percent of men with lung cancer never smoked. If only nonsmokers' deaths were counted, lung cancer would still rank in the top 10 deadliest types of the disease. The promising news, Wakelee said, is tumors often mutate differently in nonsmokers, and new drugs are being developed to target those mutations and increase survival rates. Here's a look at lung cancer funding, by the numbers. 159,480 The number of Americans projected to die of lung cancer in 2013. Lung cancer kills about four times more people than breast cancer and three times more than colorectal cancer, the second leading cancer killer. $314.6 million The amount of research dollars lung cancer received from the National Cancer Institute in 2012, making it second to breast cancer in federal funding. Breast cancer researchers received nearly twice as much. $2,000 When the amount of NCI lung cancer research funding is divided by the number lung cancer deaths, it equates to about $2,000 for each person who died last year. For breast cancer, it's more than $15,000 per death. It's about $9,000 for each prostate cancer death, and $5,000 for each colon cancer death. 15% The percentage of Americans with lung cancer who have never smoked, according to the Lung Cancer Foundation of America. Forty-five percent are former smokers, and the remaining 40 percent currently smoke. The following was originally published at DukeHealth.org by Dr. Thomas A. D’Amico on June 21st, 2011. Thomas A. D’Amico, MD, is a professor of surgery and director of the Duke Cancer Institute’s lung cancer program. He was elected chair of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network board of directors in 2010. Lung Cancer: Is “The Blame Game” Hurting our Progress?  Thomas A. D'Amico, MD Thomas A. D'Amico, MD As a thoracic surgeon, I operate on lung cancer patients every day. We discuss life-and-death issues regarding their surgeries, but we don’t usually talk about how they feel about their disease. At a recent lung cancer advocacy event, I had the opportunity to hear one of my patients tell her story. A former Division I soccer player for East Carolina University, 24-year-old Taylor Bell was diagnosed with lung cancer two weeks after her 21st birthday. She puts a very different face on lung cancer than most people expect. She’s very grateful for her survival, but she says that, even when she’s talking to survivors of other types of cancer -- to anyone, really -- when she tells people she has had lung cancer, inevitably everyone asks the same thing: “Did you smoke?” Her point of view is, “Why is that the most important thing you want to know about me?” It’s offensive to her because, number one, she didn’t smoke, and number two, what if she did? Would that mean that she deserved the disease? Assigning Blame for Lung Cancer That is the underlying assumption when many people think about lung cancer: In an international survey commissioned in 2010 by the Global Lung Cancer Coalition, 22 percent of U.S. respondents admitted they feel less sympathy for lung cancer patients than for patients with other types of cancer, because of the link to smoking. The reality is that 15 to 20 percent of folks who get lung cancer have no personal firsthand experience with tobacco. Some, like Taylor Bell, are complete non-smokers. Some have been exposed to secondhand smoke, which certainly is not their fault. If you counted just deaths from lung cancer among nonsmokers, lung cancer would still be the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States. But no one should be blamed for getting cancer, regardless of their smoking history. Most smokers first start the habit as teenagers, and by adulthood it becomes entrenched; nicotine addiction is among the hardest to overcome. The real issue is not the smoker who develops cancer; it’s how we as a society assign blame for disease. If we are to measure our sympathies for the ill by the behaviors that may have contributed to their illness, what about the patients with debilitating heart disease who have led high-stress, low-exercise lifestyles, or people with type 2 diabetes who had poor eating habits? What about the smokers who didn’t develop lung cancer but developed breast cancer, heart disease, or stroke? Would you have more sympathy for a smoker with lung cancer if you knew he had grown up with little education about the dangers of smoking? What about if the individual had a strong genetic predisposition to nicotine addiction? Stigma Slows Progress in Fight Against Lung Cancer The truth is, it’s rare that we can draw a straight line from a person’s disease to their lifestyle choices, and applying moral judgments to the ill is not only a waste of energy, but also a slippery moral slope. I believe the public-health campaign against smoking and tobacco use has had unintended consequences: not only stigma for the victims of diseases associated with smoking, but actually slowing our progress in the fight against those diseases. And that is something we need to pay attention to. The fact is that lung cancer is the most important cancer disease in our country, and indeed among all developed countries, in terms of its impact. In 2010, lung cancer caused 157,300 deaths in the United States, more than breast, prostate, and colon cancer combined, according to estimates from the American Cancer Society. In 2006, the most recent year for which we have estimates, we spent $10.3 billion in care for lung cancer patients, and the estimated loss of economic productivity due to lung cancer is $36.1 billion -- far higher than the next-highest figure (which is breast cancer, at a $12.1-billion loss). The burden of this disease to us as a society should be, in itself, enough to compel us to do everything we can to improve diagnosis and treatment. Yet lung cancer receives much less research funding than other types of cancer that cause fewer deaths. The stigma associated with lung cancer definitely takes its toll on survivors personally, and it’s possible that it also affects research funding for the disease. Using the most recent available data on National Cancer Institute research funding, lung cancer received only $1,875 per death, compared to $17,028 per breast cancer death, $10,638 per prostate cancer death, and $6,008 per colorectal cancer death. It’s impossible to read the minds of people who make decisions regarding funding for lung cancer research, but I think funding disparities can be attributed partly to a combination of the smoking stigma and ageism. If a 73-year-old person has a life-threatening disease, that’s not perceived as being as important to society as a disease that affects younger people. And an older patient population also means less patient advocacy. The fight against breast cancer, for example, has been promoted successfully because many young women who are survivors have their life to give to raising awareness. The cure rate for lung cancer is much lower than for breast cancer. So there are fewer advocates. Need for New Screening Methods and Biologic Therapies There is a need for greater research funding to advance two priorities that could make a significant difference for patients with lung cancer -- perfection of screening methods to catch more cases in the early stages, and stepped-up evaluation of biologic therapies, which can be equally as effective or more effective than chemotherapy without the overall toxicity. Improved screening is an urgent need. Today, only about 20 percent of lung-cancer cases are caught at stage one. If we could increase that to 40 percent, we would improve survival dramatically. Spiral computed tomography (CT) scan screening is a promising technique that’s being tested for patients known to be at high risk, but as a widespread tool, even CT has a drawback: the high chance of false positives. Your CT scan might show a little nodule, but that does not necessarily mean you have lung cancer, and follow-up testing for lung cancer is invasive: if you have a positive screening for a mammography, you get a needle biopsy, but a positive screen from a CT scan might lead to a surgery. We would like to be able to determine your true cancer status without having to do additional CT screens on you for the next five years or subjecting you to an unnecessary lung biopsy. A line of research that holds much promise is perfecting a method for combining CT scans with a serum or urine test that detects a protein or other biomarker. Even if we improve diagnosis, we’ll always have people who present with advanced disease, and the cure rate for those people is, frankly, dismal. One way to improve that rate is with better targeting of biologic therapies. Industry is producing these agents faster than we can test them. We need to put more effort into testing and enhancing these agents -- which could improve treatment for others cancers as well. For instance, Avastin (bevacizumab) is now known to be successful against lung cancer, but it wasn’t originally conceived as a lung cancer agent. To carry out these research priorities, we must erase the stigma that accompanies lung cancer and give the disease the full research support that its sufferers and their families deserve. In the meantime, we will count on survivors such as Taylor Bell, who handles the smoking question with grace. After she tells people that no, she never smoked, the second question usually is: “Well, how did you get it?” Her response: “Why does anyone get cancer?” 6/26/2013 More #Research Needs to Be Done On Treatment For #LungCancer Among Non-Smoking #WomenRead NowThis story originally published by Sam Goodwin on HGNG.com on 6/26/13.  The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) finds that much more research needs to be done on treatment given to non-smoking women for lung cancer. An estimated 516,000 women worldwide are affected by lung cancer and 100,000 of these women are from the United States. Up until now, women with lung cancer have been given the same treatment as men. However, numerous studies have highlighted different characteristics of lung cancer in women. Hence, there is a need for more research to be done on lung cancer treatment given to women, especially those who don't smoke, states the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC). Researchers from the University of Toulouse III in France looked into the clinical, pathological and biological characteristics of lung cancer in 140 women. They found that 63 participants had never smoked in their lives while 77 were either former or current smokers. Researchers compared the findings of both groups and found differential genetic alteration repartition in women according to their tobacco status. Around 50.8 percent of women who had never smoked displayed an EGFR mutation while only 10.4 percent of current/former smokers showed the same mutation. However, 33.8% of current/former smokers showed K-Ras mutation while only 9.5 percent of women who had never smoked showed this form of mutation. The researchers also observed a higher percentage of estrogen receptors (ER) α expression in patients who never smoked when compared with smokers. This led researchers to conclude that lung cancer in women who have never smoked is more frequently associated with EGFR mutations and estrogen receptor (ER) over expression. "These findings underline the possibility of treatment for women who have never smoked with drugs to target hormonal factors, genetic abnormalities, or both," the authors say. The study is published in the July issue of the Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 3/26/2013 The Lung Cancer Living Room - Personalizing Your Care - Dr. David Gandara - Feb. 19, 2013Read NowIn his second visit to the Lung Cancer Living Room, Dr. David Gandara of UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center, discusses how your cancer is unique and that your approach to treating it should be too. He talks about discovering your 'molecular fingerprint' and how that information will help guide you through your unique cancer 'journey'. He also talks about some of the latest findings regarding "Tumor Darwinism"- how your cancer's molecular signature can evolve over time, as well as some of the latest research funded by the Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation using mouse models to test new forms of treatment. He closes with a discussion of the importance of getting involved in clinical trials. The bottom line he says is that empowered patients live longer. It is a visit filled with lots of useful detailed information, and a clear message of hope and progress.

Learn more about The Lung Cancer Living Room here. |

Details

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed