|

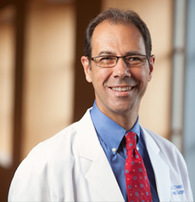

The following was originally published at DukeHealth.org by Dr. Thomas A. D’Amico on June 21st, 2011. Thomas A. D’Amico, MD, is a professor of surgery and director of the Duke Cancer Institute’s lung cancer program. He was elected chair of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network board of directors in 2010. Lung Cancer: Is “The Blame Game” Hurting our Progress?  Thomas A. D'Amico, MD Thomas A. D'Amico, MD As a thoracic surgeon, I operate on lung cancer patients every day. We discuss life-and-death issues regarding their surgeries, but we don’t usually talk about how they feel about their disease. At a recent lung cancer advocacy event, I had the opportunity to hear one of my patients tell her story. A former Division I soccer player for East Carolina University, 24-year-old Taylor Bell was diagnosed with lung cancer two weeks after her 21st birthday. She puts a very different face on lung cancer than most people expect. She’s very grateful for her survival, but she says that, even when she’s talking to survivors of other types of cancer -- to anyone, really -- when she tells people she has had lung cancer, inevitably everyone asks the same thing: “Did you smoke?” Her point of view is, “Why is that the most important thing you want to know about me?” It’s offensive to her because, number one, she didn’t smoke, and number two, what if she did? Would that mean that she deserved the disease? Assigning Blame for Lung Cancer That is the underlying assumption when many people think about lung cancer: In an international survey commissioned in 2010 by the Global Lung Cancer Coalition, 22 percent of U.S. respondents admitted they feel less sympathy for lung cancer patients than for patients with other types of cancer, because of the link to smoking. The reality is that 15 to 20 percent of folks who get lung cancer have no personal firsthand experience with tobacco. Some, like Taylor Bell, are complete non-smokers. Some have been exposed to secondhand smoke, which certainly is not their fault. If you counted just deaths from lung cancer among nonsmokers, lung cancer would still be the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States. But no one should be blamed for getting cancer, regardless of their smoking history. Most smokers first start the habit as teenagers, and by adulthood it becomes entrenched; nicotine addiction is among the hardest to overcome. The real issue is not the smoker who develops cancer; it’s how we as a society assign blame for disease. If we are to measure our sympathies for the ill by the behaviors that may have contributed to their illness, what about the patients with debilitating heart disease who have led high-stress, low-exercise lifestyles, or people with type 2 diabetes who had poor eating habits? What about the smokers who didn’t develop lung cancer but developed breast cancer, heart disease, or stroke? Would you have more sympathy for a smoker with lung cancer if you knew he had grown up with little education about the dangers of smoking? What about if the individual had a strong genetic predisposition to nicotine addiction? Stigma Slows Progress in Fight Against Lung Cancer The truth is, it’s rare that we can draw a straight line from a person’s disease to their lifestyle choices, and applying moral judgments to the ill is not only a waste of energy, but also a slippery moral slope. I believe the public-health campaign against smoking and tobacco use has had unintended consequences: not only stigma for the victims of diseases associated with smoking, but actually slowing our progress in the fight against those diseases. And that is something we need to pay attention to. The fact is that lung cancer is the most important cancer disease in our country, and indeed among all developed countries, in terms of its impact. In 2010, lung cancer caused 157,300 deaths in the United States, more than breast, prostate, and colon cancer combined, according to estimates from the American Cancer Society. In 2006, the most recent year for which we have estimates, we spent $10.3 billion in care for lung cancer patients, and the estimated loss of economic productivity due to lung cancer is $36.1 billion -- far higher than the next-highest figure (which is breast cancer, at a $12.1-billion loss). The burden of this disease to us as a society should be, in itself, enough to compel us to do everything we can to improve diagnosis and treatment. Yet lung cancer receives much less research funding than other types of cancer that cause fewer deaths. The stigma associated with lung cancer definitely takes its toll on survivors personally, and it’s possible that it also affects research funding for the disease. Using the most recent available data on National Cancer Institute research funding, lung cancer received only $1,875 per death, compared to $17,028 per breast cancer death, $10,638 per prostate cancer death, and $6,008 per colorectal cancer death. It’s impossible to read the minds of people who make decisions regarding funding for lung cancer research, but I think funding disparities can be attributed partly to a combination of the smoking stigma and ageism. If a 73-year-old person has a life-threatening disease, that’s not perceived as being as important to society as a disease that affects younger people. And an older patient population also means less patient advocacy. The fight against breast cancer, for example, has been promoted successfully because many young women who are survivors have their life to give to raising awareness. The cure rate for lung cancer is much lower than for breast cancer. So there are fewer advocates. Need for New Screening Methods and Biologic Therapies There is a need for greater research funding to advance two priorities that could make a significant difference for patients with lung cancer -- perfection of screening methods to catch more cases in the early stages, and stepped-up evaluation of biologic therapies, which can be equally as effective or more effective than chemotherapy without the overall toxicity. Improved screening is an urgent need. Today, only about 20 percent of lung-cancer cases are caught at stage one. If we could increase that to 40 percent, we would improve survival dramatically. Spiral computed tomography (CT) scan screening is a promising technique that’s being tested for patients known to be at high risk, but as a widespread tool, even CT has a drawback: the high chance of false positives. Your CT scan might show a little nodule, but that does not necessarily mean you have lung cancer, and follow-up testing for lung cancer is invasive: if you have a positive screening for a mammography, you get a needle biopsy, but a positive screen from a CT scan might lead to a surgery. We would like to be able to determine your true cancer status without having to do additional CT screens on you for the next five years or subjecting you to an unnecessary lung biopsy. A line of research that holds much promise is perfecting a method for combining CT scans with a serum or urine test that detects a protein or other biomarker. Even if we improve diagnosis, we’ll always have people who present with advanced disease, and the cure rate for those people is, frankly, dismal. One way to improve that rate is with better targeting of biologic therapies. Industry is producing these agents faster than we can test them. We need to put more effort into testing and enhancing these agents -- which could improve treatment for others cancers as well. For instance, Avastin (bevacizumab) is now known to be successful against lung cancer, but it wasn’t originally conceived as a lung cancer agent. To carry out these research priorities, we must erase the stigma that accompanies lung cancer and give the disease the full research support that its sufferers and their families deserve. In the meantime, we will count on survivors such as Taylor Bell, who handles the smoking question with grace. After she tells people that no, she never smoked, the second question usually is: “Well, how did you get it?” Her response: “Why does anyone get cancer?”

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed